Fantastic event in Bristol this week on neuroscience for change management. Brilliant speaker, Tom Flatau from Team Working International gave us insight and led us through discussions on the practical application in managing change of how the brain works.

My key takeaways were: Culture isn’t the biggest driver for decisions By understanding how the brain works, you get an insight into what can inadvertently alienate people. Our brains create meaning from every experience we have, everything we see and hear and that meaning is affected by our previous experiences.

For those of us leading change across multiple countries, it was interesting to hear how consistent the brain is in how it behaves, irrespective of culture.

My conclusion is that whilst there are cultural rituals that sit on top of the basic operation of the brain, if I can use the principles of neuroscience to guide my interactions, then it doesn’t matter so much which country I am working in.

Part of this was the statistic behind how we make up our minds. 95% of our decision making is based on emotion, and only 5% is drawn from facts and information. From the outset it is important to create positive feelings about the change, create an environment where people feel valued, feel safe to share their thoughts and hear about the opportunities created by the change. Any negativity from the start will be hard to shift, because however many positive facts you put forward, the emotional part of the brain has already decided that the change is bad news!

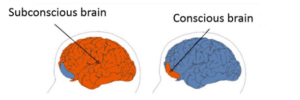

We looked at the parts of the brain that govern our conscious and sub-conscious decision making.

It is the non-conscious brain that makes snap decisions and although our conscious brain can use

facts and figures to override our initial decision, it rarely does so. The original snap decision is the

one we stick with. This is confirmation bias.

Use emotion to drive decisions

This led us to a discussion of marketing and advertising (essential change management skills) and the research that shows emotional campaigns are twice as effective as rational campaigns. We talk

about the importance of engaging hearts and minds, but I enjoyed seeing some of the research that

backs this up as it helps me convince the executives that I am working with that storytelling is not

just “soft and fluffy” but is an effective tool.

We talked about the need to share vulnerability as part of this emotional pull. This made sense to

me as part of the Certified Local Change Agents Course deals with influencing styles including

“Sharing Disclosure” which is a way of drawing people towards your viewpoint by sharing your

feelings. This builds authenticity which generates trust.

As a result of this part of the evening, I had an idea about how to communicate a new change

programme I am responsible for in the Middle East. Instead of sending the usual emails about what

is going to happen, what the schedule is and who is involved, I am going to start with video clips

telling stories about how this change programme has been successful in other countries. I am going

to tell stories that tap into my audiences’ inner beliefs about what is important, which in this case

will be reassurance that this is global best practice, learning from other organisations who are doing

change better than they are.

Make friends

We moved onto talking about the threat response, which is the first response of our brain to any

situation. 96% of our brain is the sub-conscious part that makes snap decisions, and its first decision

is to decide “friend or foe?” If we decide someone is a friend, we give what they are saying a chance,

we give them the benefit of the doubt. If we decide someone is an enemy, we immediately argue,

disagree and resist what they are telling us. It makes sense to form relationships and establish

ourselves as friends before we start communicating any key messages about our change. This means

identifying things we have in common and building in the time for talking and forming relationships

into how we work. This is an up-front cost that pays dividends later in the change programme when I

don’t have to spend so much time overcoming resistance to change. I am trusted because I am

regarded as a friend not a foe.

Conclusion

Neuroscience continues to be an excellent source of ideas for change professionals. If you want

more information, these are two great sources: https://www.koganpage.com/product/neuroscience-for-organizational-change-9780749474881 and

https://www.edbatista.com/2010/03/scarf.html